Frameworks and Follow-up

During my first year of teaching after a career-switch, my county assigned me a mentor. I was just starting on my required coursework for certification, and this retired teacher observed my classes periodically and helped me navigate my new profession. She helped me out tremendously. However, there is one meeting I remember especially well because, for once, she asked me to do something that made teaching harder rather than easier. She suggested that I should start and end feedback on students’ projects with positive comments to “cushion” the tougher criticism in the middle. I had always praised students’ efforts, but there were times when I really struggled to come up with enough positive comments that did not sound ridiculous to follow her advice. I knew that if I found them phony, so would my students.

For as long as I was in the classroom, I struggled with this “compliment sandwich” framework.

It seems I was not alone in my discomfort. Lots of people don’t like this approach in education or in the business world. The compliment sandwich can be confusing. If there is so much to praise at the start and at the end of the feedback, are revisions really necessary? And, as I’ve said, some of the positive comments can ring hollow. If students realize the compliments are not genuine, they can lose trust in the relationship. How can students trust a teacher who blows hot air about their work? No matter what you see in feel-good social media posts, a student-teacher relationship is not really about funny handshakes at the classroom door, nor is it about false admiration. Students want to know their teachers are telling them the truth.

Recently I have been reading about wise feedback, and I think this framework fits in perfectly with project-based learning. Wise feedback is comprised of three parts. First, reiterate the high standards and expectations for the work. Second, state the belief that students can meet those standards. In this particular context, these first two steps are a reminder to the students of the standards and expectations they themselves agreed to at the start of the project. Third, suggest concrete and actionable steps to achieve the standards, assuring students they will have the support they need (I’ve included some examples below).

The research on the use of the wise feedback framework points to an increase in trust and allows students to see themselves as academically capable. It also shows that the use of the framework leads to an increase in the likelihood that students will act upon the feedback they receive, revising and improving their work. And while most of the research has been done around writing assignments, the framework should have similar effects in other contexts. As I pointed out before, the fact that the goals and standards for projects are set by the students in partnership with the teacher makes this framework a logical choice for giving students feedback.

Since the wise framework has been mostly applied in the context of writing assignments, the feedback itself has often involved teachers writing their comments as they read papers — without students being present. Yet there are no rules requiring feedback to be given only in this asynchronous form. For projects, assessment and feedback should be a conversation that happens during the meetings I discussed in the previous post of this series. As the teacher and students discuss how the project is going, the teacher can record notes about the feedback in a shared online document. This document then becomes a record of how the project is evolving and progressing toward established goals.

At each meeting, the teacher and the students review the notes from the previous meeting to ensure any problems have been addressed. Then the teacher provides new feedback focusing on how the project stands at the moment. Finally, the team and the teacher discuss what comes next, determining concrete actions to continue making progress. Throughout, the feedback and next steps should be formulated based on the goals set at the start of the project.

Let’s look at our water cycle interactive museum display project introduced at the start of this series. During the building phase of the project, the teacher meets with a team that is working simultaneously on building a landscape model out of crafting materials, and coding the buttons that will play audio recordings and turn on lights to explain excessive runoff due to urbanization, roads, and parking lots. The students show the landscape and code to the teacher, and explain what they’re working on. They also share what they plan to do during the next couple of class blocks. The teacher takes notes on what he sees. He notes that the landscape model is likely too flimsy to support the buttons and wires necessary to provide the interactivity the students intend. The audio messages that play when the buttons are pressed contain good information, but the recordings have a lot of background noise. The code that lights the LEDs to draw attention to different areas of the display blink several times to ensure visitors know where to look, but the students have used red and green lights which may cause accessibility issues for colorblind people. During the meeting, the teacher also notices that two team members seem to be having a disagreement.

Using the wise framework, the teacher can point to the flimsy landscape and remind student that a sagging or torn display does not meet the standards the class set at the start of the project, suggesting that the team should brainstorm ways to strengthen or support the model more effectively. The team lets the teacher know they have already noticed the problem and had planned on using a couple of empty boxes under the display to add support. The teacher offers to bring empty boxes from home in case they need more. Then the teacher points to the issue with the audio recordings and suggests that students re-record their narratives in a quiet space, offering to write a pass to the library if the team needs it. Finally, the teacher addresses the color of the LEDs, which causes one student to stomp her foot and another to say, “I said that, but she wanted Christmas colors!” Since one of the goals set by the class is effective and equitable teamwork, the teacher reminds the students that he is available to help mediate disagreements.

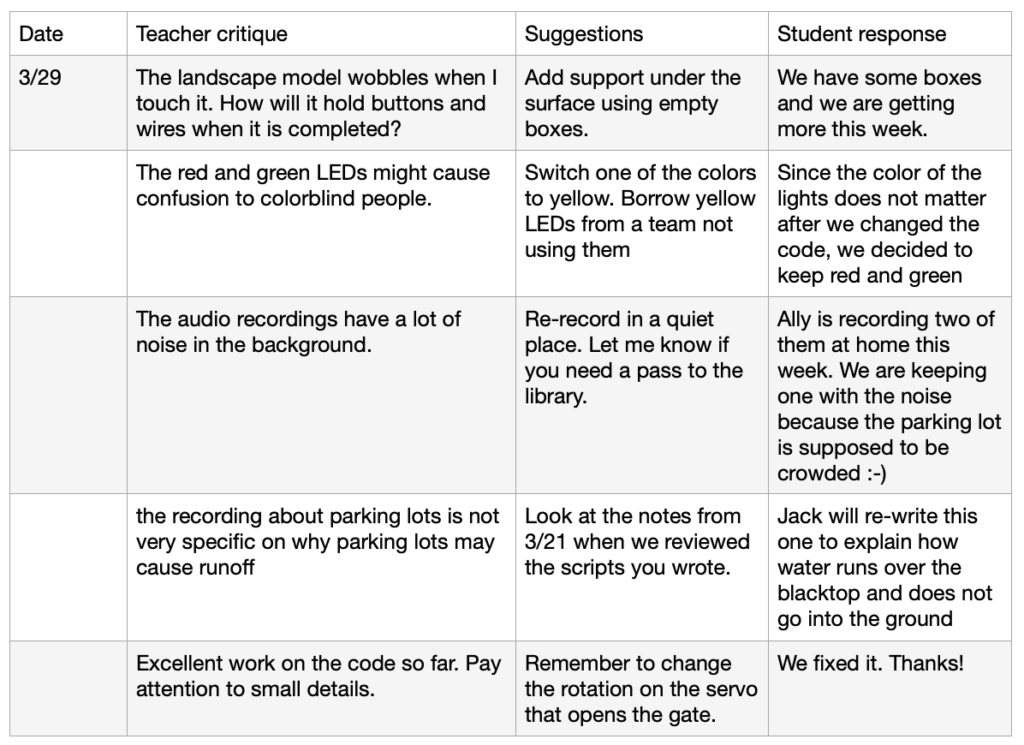

As the teacher discusses each of these points, he takes notes about the conversation — including the details of what was proposed and what resources are needed — in a shared online spreadsheet. The students can reference the notes whenever they are working if they need a reminder of what was discussed. The spreadsheet also features a column where students can respond to feedback between meetings. They can update the document as they make adjustments to their project, or they can explain why they have decided to do things differently than they proposed during the conference.

This last point is important. Students need contexts in which they are invited to disagree with their teachers. In most classrooms, students are expected to do as they are told without question, but that offers them no opportunities to develop important critical and communication skills. Through this process, on the other hand, students are encouraged to defend and justify their ideas, disagreeing in a respectful and constructive way. It is an excellent skill for students to develop.

This is what the shared document might look like after this meeting. While the agreed-upon goals and high expectations are not explicitly mentioned in the document, they would have been referenced during the meeting.

At the start of the series I suggested that structuring projects to allow for frequent feedback could help a teacher address the lack of grades in the grade book. Let’s address this particular issue. There could be a grade attached to each of these meetings. For example, each meeting could have a grade made up of three elements. First, have students addressed feedback from the previous meeting adequately? Second, have students progressed towards the final goals? Third, how is the team working together?

Whether these grades are assigned or not, this feedback framework provides guardrails to keep the project on track to help students meet their learning goals. Giving students formative assessment with actionable feedback while the project is in progress greatly reduces the possibility of a disappointing finished product. The transparency of the process throughout ensures that students are aware of the quality of their work and see their progress, developing metacognitive skills.

Planning and executing long-term creative projects with students can be a daunting proposition for many teachers. I hope this series of posts encourages at least a few people to take the plunge. And when you do, I’d love to hear about it.