In April of 2019 I left my job of twelve years and spent the following five months focusing on my health. I returned to work in September only to be sent to work from home in early March. In August I chose not to return to in-person teaching and left my job. I’ve been working on independent projects since then. This means that I have spent 20 out of the past 26 months mostly at home. Lucky for me, being at home is not a burden at all. But, as I prepare to return to full-time, in-person work in just a couple of weeks, I’ve been thinking about what’s kept me going during these 20 months at home. Of course, my husband and my children have been integral to my wellbeing. But so has our house and its immediate surroundings. Our yard, our garden, and the surrounding woods have been a constant source of joy and beauty.

A little over six years ago, when we moved into our home, I had been taking insect pictures for a few years. It was something that filled a gap in my life. I had never had a hobby. I mean, I have collected stamps, knitted, baked, danced, whatever, but I never went beyond the basics. Macrophotography was different from the beginning because I discovered it at a time when I really needed something to keep me going. I started taking macro pictures with my phone and a clip-on attachment because it was what I had handy. I could have upgraded my equipment, learned to set up and light complicated shots using much more advanced cameras, filters, lamps, light diffusers, etc. I have some of these things, but I like the spontaneity of a single handheld shot, and my phone lets me get into some tight spots. I have chosen to keep using my phone, upgrading it to make use of the ever-improving image sensors and buying higher quality clip-on lenses, but I have not made the process any more complex. As a family, we also chose to “upgrade” my stage. Moving into a home surrounded by a creek, a pond, and several acres of woods was a choice we made just so I could explore without having to drive anywhere.

To me, my photography has not been just about the pictures. It has been about the learning that comes with them. There are hundreds of thousands of organisms surrounding us every day. Most of us are unaware they even exist. I was unaware just like everyone else until I started looking for subjects to photograph. As I found new creepy crawlies, I read about them. I built an online space to learn and share. I joined iNaturalist during a trip to San Diego and started uploading images. I already knew what some creatures were. For others, I relied on the artificial intelligence engine and the experts in the community to help me figure out their identities.

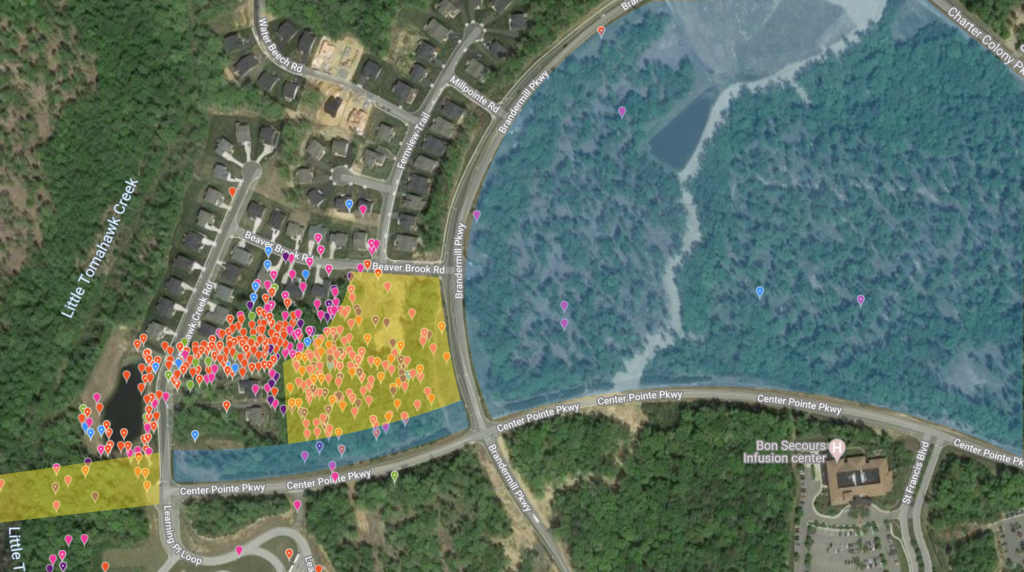

As I have learned about tiny organisms, I have also learned about the damage humans do to them without even realizing it. Over the past few years we have transformed a boring green lawn into an ecosystem full of flowering plants and trees. We have filled a patch damaged by construction equipment into a wildflower field. We have built a garden where we share our tomatoes and eggplants with lots of little visitors, some more destructive than others. I have piled up fallen tree limbs along the edge of the woods to give mushrooms and slime molds a place to grow. Almost every day I go see what’s new on our property and the woods around us. Unfortunately, much of those woods are now being cleared for construction.

But my focus on my subjects and my environment doesn’t mean I don’t think about photography and improving what I do. When I first started taking pictures of insects, I fired off shots in a rush. After all, insects are skittish and I have to be about an inch away from them to get them in focus. This made for poor framing, and while I could fix some of that with cropping and rotating, there’s only so much I could do. Over the years, I have learned more about critters that has helped me take better photos. Some move slower when they are feeding or mating. Most of them move slowly in cool weather. Some stay in the same area for much of their lives and get used to me hanging around them. Some just don’t mind me at all. And then there are the things that can’t move away, like plants, mushrooms, and slime molds. In those cases, I’ve had to learn to be more selective in what I photograph. After all, if I’m not careful, I end up with 400 pictures of the same patch of fungus. Rather than just being excited about seeing a specimen, I’ve begun to look for an interesting setting, a composition combining more than one species, or lighting that gives the frame a special something. Sometimes, it is even possible to do this with insects, waiting for the right moment to catch it tilting its head, seeming to glance at me with an attitude.

Through all this I have had some very simple rules. I don’t collect what I shoot. I leave plants where they are unless I’m harvesting something I’ll eat. I don’t kill or chill my insects. I might bend a twig or fold a leaf to get a better angle or better lighting, but I shoot everyone in place and leave them where I found them — a choice facilitated by my embrace of phone-based photography . I don’t amp up the color or contrast beyond minor fixes to compensate for bad lighting. I want to represent nature as naturally as possible.

The natural representation of what I find requires that I provide a place for those organisms so I can enjoy photographing them. I know that in certain ways, I’ve been part of a larger problem. I chose to purchase a home that is a product of urban sprawl, which led to my lot and my entire subdivision being cleared. But now that I’m here, I’m working to restore some balance. Replacing an unsustainable grass monoculture with planting areas full of native species has been one of our largest home improvement projects. Letting weeds grow rather than engaging in wide-scale napalming probably makes some of our neighbors unhappy, but I’m okay with that as long as it creates a more vibrant and sustainable ecosystem.

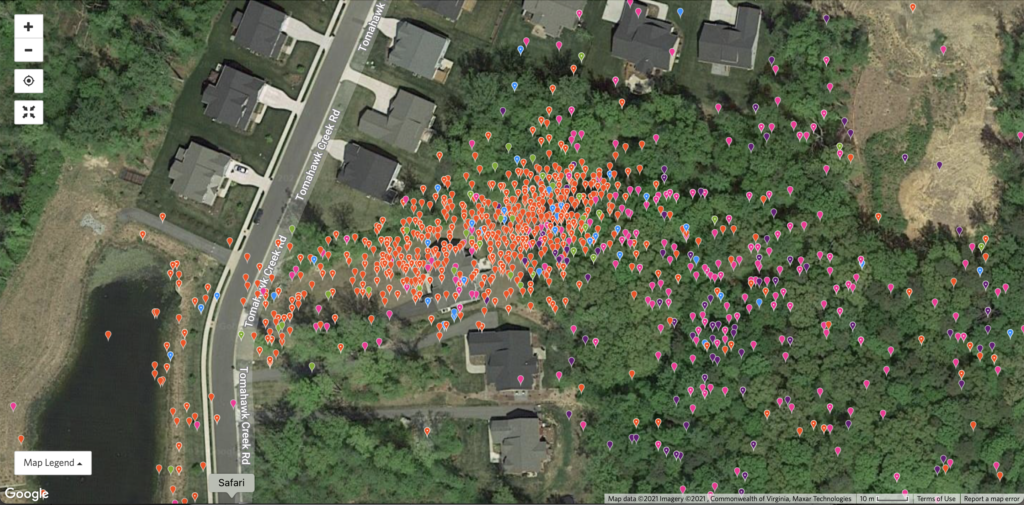

Over the past 26 months I have taken thousands of photographs of hundreds of species. I have learned so much about insects, plants, fungi, nesting habits of birds … but also about fertilizers, invasive species, and the impact of my neighbors’ use of pesticides. I have learned to be patient, waiting for a bug to get used to my hand holding on to a leaf, or waiting for a mushroom to pop open its gills over several hours. I have learned to share our zucchini plants with helmeted squash bugs because some birds will come by to feed on the bugs. I have learned that it is possible not to be bored even when I spend 99% of my time within 200 yards of my home if I keep my eyes open. I have uploaded over 2200 images to the iNaturalist website and have over 960 different species identified and verified among those images. I could spend a lifetime here and I’d still be finding new subjects to photograph, but only if I make a home for them. This becomes even more important as more of my surroundings are cleared for construction.

If circumstances had forced me to spend 20 months at home a decade ago, I wouldn’t have survived. But by becoming a better partner with the natural world, I have. My reward for providing a home for other species is that they have provided an outlet that has contributed in no small part to my wellbeing and happiness over the past two years.